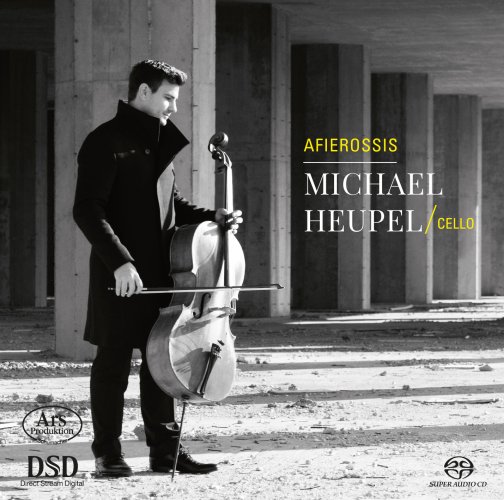

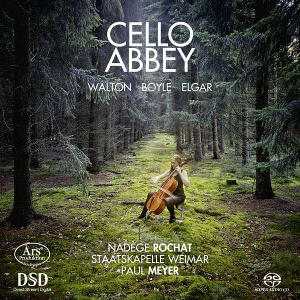

"For many years we have been waiting for a worthy successor to Jacqueline Dupré’s (remastered and stereo only) Hi-res recording of Elgar’s Cello concerto. And now, within a few months, we have two new entries. This latest version, played by Franco-Swiss cellist, Nadège Rochat, faces stiff competition from Johannes Moser, who in the meantime succeeded in establishing himself as an obvious choice, drawing additional profit from a warm and spacious recording, signed Pentatone/Polyhymnia.

This is Nadège Rochat’s third album for ARS-Produktion. Under the title ‘Cello Abbey’ - where abbey stands for country house - she combines three pieces for cello and orchestra written by British contemporaries, whom she has come to appreciate during her studies at the Royal Academy of Music in London. Next to Elgar we get Walton’s cello concerto and the world premiere of an Elegy for Cello and Orchestra (1913) from a hardly known, but all the same delightfully pastoral Irish (in those days still part of Britain) composer, Ina Boyle.

For those who are, and I suspect there are many, including me, not familiar with Boyle’s musical style, I copy the following from Elizabeth Maconchy’s essay on Ina Boyle (TCD, Dublin, 1974): “Her music is predominantly quiet and serious, never brilliant, though it has its moments of wit or passion. In idiom it is closest perhaps to Vaughan Williams in his early middle period - but it is not just a pale reflection of his style; her music always speaks with a personal tone of voice, which at its best can express deep feeling by simple means”.

To start at the end, the Elgar concerto: Rochat treats us with a feminine approach reminiscent of Dupré. Her technical skills never stand in the way of delicate bowing and subtle legato. She may not be as powerful as Moser, but her musical language is elegant, light and colourful, giving a detailed and soul searching account of one of the highlights of 20th century cello concerti.

The second movement is lightheartedly portrayed and in the adagio Rochat explores the beauty with a sense of longing. Where Moser overlooks the Malvern Hills, Rochat seeks a haven in a sunny rose garden. Indeed, two different approaches. I had not heard anything from Rochat before and I must say that it is a pleasant surprise, as is the quality of the young French clarinetist/conductor Paul Meyer and the Weimar Staatskapelle.

For further Hi-res comparison (and completeness sake) I had another version at my disposal with Yoohong Lee (cello), the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Yehudi Menuhin (conductor) from the RCO-series, released by membran. It’s certainly not bad, but a bit heavy handed. Too much drama, too little country side. A multi-channel sound, probably reconstituted from a whole array of individually taped microphones, giving an artificial surround and an overpowering soloist. No match for either of the other two.

Boyle is not high on the list of composers. My research suggests several reasons, the more important being the rural environment which was hers for a long time, as well as the fact that musical life in the Irish part of Britain was not so well developed, remaining at the level of folk music, with no inspiration to innovate as in continental Europe (her friend Elizabeth Maconchy, who was more attracted to the likes of Bartók and Janácek, tried in vain to make her move to London, which she eventually did but for a while, meeting with Ralph Vaughan Williams).

Ms Rochat tells us in the liner notes how she stumbled on Boyle when searching for cello scores to widen her repertoire and how she subsequently found in her an ‘accomplice in music’. This personal identification has clearly led to the glowing account of the Elegy. It is a short piece (07:24) with a hint to English rule preceding the Irish War of Independence 1919-1921. Good to have it on record.

Rochat faces stiff competition, too, in William Walton’s cello concerto. But what I found quite remarkable is that both Poltéra (BIS) and Rochat (ARS) portray themselves more English than Watkins (Chandos). Watkins gives a fine account, but I feel that in comparison the two Swiss artists somehow dig deeper in the score, unraveling the sheer lyrical beauty and the intrinsic musical values, without becoming too much inward looking. On the other hand: In terms of recording, Poltéra and Rochat are placed rather prominently, whereas Watkins is much better integrated in the overall musical fabric.

Mademoiselle Rochat is undeniably at her best in Walton. In spite of him being seen by his colleagues and musicologists as un ‘enfant terrible’ of English music because of his talent and attributed ‘avant garde’ modernism, the concerto firmly relates to late English romantic tradition. Some critics judged it even ‘old fashioned’ and possibly rightly so. But that is not the same as saying that is isn’t any good. It’s a product of meticulous craftsmanship and inventive scoring with the fast movement in the middle and two solo parts in the third. Scholars have described the concerto as subdued, lyrical, bittersweet and introspective. Whatever its description, listening proves that it contains all the elements of a master piece.

In Rochat’s personal view it conveys an optimistic message, like saying ‘yes’ to the world. In my view such feelings are not only free and permitted, but are also a clear sign of artistry, showing insight and character. It sheds a different light on the score, needing and getting a poetical reading; searching for the positive meaning behind the notes. Refined and elegant playing plus ‘twinkling’ orchestral support make the first movement a rare experience, getting close to Poltéra’s, while she, with her youthful compassion and infectious élan, surpasses - as far as I’m concerned - the admittedly perfect but nonetheless more traditional account of Watson.

The virtuoso second movement poses no problem for Rochat. It is light-footed with no hint of aggressiveness (as for instance in Yo Yo Ma’s reading on CBS Masterworks, which I consulted ‘pour aquit de conscience’). I’m furthermore of the opinion that there isn’t much difference between the BBC players and those of Weimar, but if so, than they largely make up for such difference through committed engagement and inspired enthusiasm.

Rochat’s perfect pitch and judicious phrasing sublimate in the final movement where she convincingly states her credentials in the two solo improvisations, bringing, in collective harmony with Paul Meyer and his musicians, the concerto in its closing epilogue to a memorable end.

As for the DSD recording: ARS-Produktion does not disappoint. Clarity is excellent and the depth of the sound stage realistic. But in order to avoid a too forward projection of the soloist I recommend keeping the surround speakers under control." Quelle: hr-audio.net

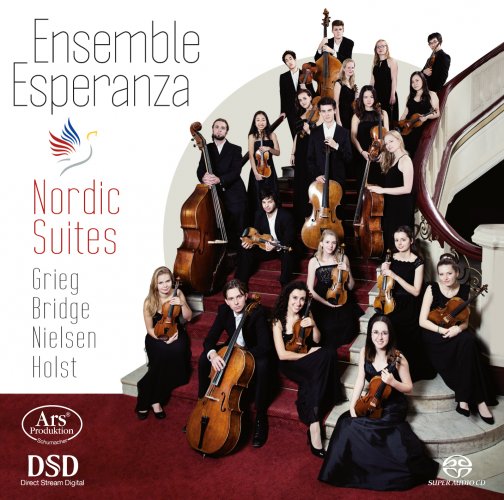

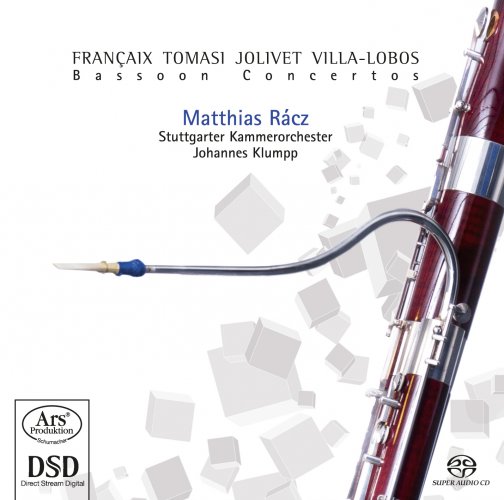

Die CD ist beim Label "Ars Produktion" erschienen.

MR-Musikproduktion: Recording Engineer